|

A book is a set or collection of written, printed, illustrated, or blank sheets, made of paper, parchment, or other various material, usually fastened together to hinge at one side. A single sheet within a book is called a leaf, and each side of a leaf is called a page. A book produced in electronic format is known as an electronic book (e-book). Books may also refer to works of literature, or a main division of such a work. In library and information science, a book is called a monograph, to distinguish it from serial periodicals such as magazines, journals or newspapers. The body of all written works including books is literature. In novels and sometimes other types of books (e.g. biographies), a book may be divided into several large sections, also called books (Book 1, Book 2, Book 3, etc.). A lover of books is usually referred to as a bibliophile, a bibliophilist, or a philobiblist, or, more informally, a bookworm. A store where books are bought and sold is a bookstore or bookshop. Books can also be borrowed from libraries. In 2010, Google estimated that there were approximately 130 million unique books in the world

Etymology The word book comes from Old English "bōc" which itself comes from the Germanic root "*bōk-", cognate to beech. Similarly, in Slavic languages (e.g. Russian, Bulgarian and Macedonian) "буква" (bukvaâ€â€"letter") is cognate to "beech". It is thus conjectured that the earliest Indo-European writings may have been carved on beech wood. Similarly, the Latin word codex, meaning a book in the modern sense (bound and with separate leaves), originally meant "block of wood". Main article: History of books

Antiquity

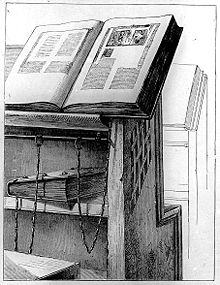

Sumerian language cuneiform script clay tablet, 2400–2200 BC When writing systems were invented in ancient civilizations, nearly everything that could be written uponâ€â€stone, clay, tree bark, metal sheetsâ€â€was used for writing. Alphabetic writing emerged in Egypt about 5,000 years ago. The Ancient Egyptians would often write on papyrus, a plant grown along the Nile River. At first the words were not separated from each other (scriptura continua) and there was no punctuation. Texts were written from right to left, left to right, and even so that alternate lines read in opposite directions. The technical term for this type of writing is ’boustrophedon,’ which means literally ’ox-turning’ for the way a farmer drives an ox to plough his fields. Main article: Scroll

Egyptian papyrus showing the god Osiris and the weighing of the heart. Papyrus, a thick paper-like material made by weaving the stems of the papyrus plant, then pounding the woven sheet with a hammer-like tool, was used for writing in Ancient Egypt, perhaps as early as the First Dynasty, although the first evidence is from the account books of King Neferirkare Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2400 BC). Papyrus sheets were glued together to form a scroll. Tree bark such as lime (Latin liber, from which also comes library) and other materials were also used. According to Herodotus (History 5:58), the Phoenicians brought writing and papyrus to Greece around the 10th or 9th century BC. The Greek word for papyrus as writing material (biblion) and book (biblos) come from the Phoenician port town Byblos, through which papyrus was exported to Greece. From Greek we also derive the word tome (Greek: τόμος), which originally meant a slice or piece and from there began to denote "a roll of papyrus". Tomus was used by the Latins with exactly the same meaning as volumen (see also below the explanation by Isidore of Seville). Whether made from papyrus, parchment, or paper, scrolls were the dominant form of book in the Hellenistic, Roman, Chinese, and Hebrew cultures. The more modern codex book format form took over the Roman world by late antiquity, but the scroll format persisted much longer in Asia. Main article: Codex

Papyrus scrolls were still dominant in the 1st century AD, as witnessed by the findings in Pompeii. The first written mention of the codex as a form of book is from Martial, in his Apophoreta CLXXXIV at the end of the century, where he praises its compactness. However the codex never gained much popularity in the pagan Hellenistic world, and only within the Christian community did it gain widespread use. This change happened gradually during the 3rd and 4th centuries, and the reasons for adopting the codex form of the book are several: the format is more economical, as both sides of the writing material can be used; and it is portable, searchable, and easy to conceal. The Christian authors may also have wanted to distinguish their writings from the pagan texts written on scrolls.

A Chinese bamboo book Wax tablets were the normal writing material in schools, in accounting, and for taking notes. They had the advantage of being reusable: the wax could be melted, and reformed into a blank. The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman pugillares) is a possible precursor for modern books (i.e. codex). The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) also suggests that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets. In the 5th century, Isidore of Seville explained the relation between codex, book and scroll in his Etymologiae (VI.13): "A codex is composed of many books; a book is of one scroll. It is called codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (codex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock, because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches." Main article: Manuscript

Folio 14 recto of the 5th century Vergilius Romanus contains an author portrait of Virgil. Note the bookcase (capsa), reading stand and the text written without word spacing in rustic capitals. The fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century A.D. saw the decline of the culture of ancient Rome. Papyrus became difficult to obtain due to lack of contact with Egypt, and parchment, which had been used for centuries, became the main writing material. Monasteries carried on the Latin writing tradition in the Western Roman Empire. Cassiodorus, in the monastery of Vivarium (established around 540), stressed the importance of copying texts. St. Benedict of Nursia, in his Regula Monachorum (completed around the middle of the 6th century) later also promoted reading. The Rule of St. Benedict (Ch. XLVIII), which set aside certain times for reading, greatly influenced the monastic culture of the Middle Ages and is one of the reasons why the clergy were the predominant readers of books. The tradition and style of the Roman Empire still dominated, but slowly the peculiar medieval book culture emerged. Before the invention and adoption of the printing press, almost all books were copied by hand, which made books expensive and comparatively rare. Smaller monasteries usually had only a few dozen books, medium-sized perhaps a few hundred. By the 9th century, larger collections held around 500 volumes and even at the end of the Middle Ages, the papal library in Avignon and Paris library of Sorbonne held only around 2,000 volumes.

Burgundian author and scribe Jean Miélot, from his Miracles de Notre Dame, 15th century. The scriptorium of the monastery was usually located over the chapter house. Artificial light was forbidden for fear it may damage the manuscripts. There were five types of scribes:

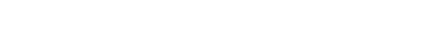

The bookmaking process was long and laborious. The parchment had to be prepared, then the unbound pages were planned and ruled with a blunt tool or lead, after which the text was written by the scribe, who usually left blank areas for illustration and rubrication. Finally, the book was bound by the bookbinder. Different types of ink were known in antiquity, usually prepared from soot and gum, and later also from gall nuts and iron vitriol. This gave writing a brownish black color, but black or brown were not the only colors used. There are texts written in red or even gold, and different colors were used for illumination. Sometimes the whole parchment was colored purple, and the text was written on it with gold or silver (for example, Codex Argenteus). Irish monks introduced spacing between words in the 7th century. This facilitated reading, as these monks tended to be less familiar with Latin. However, the use of spaces between words did not become commonplace before the 12th century. It has been argued that the use of spacing between words shows the transition from semi-vocalized reading into silent reading. The first books used parchment or vellum (calf skin) for the pages. The book covers were made of wood and covered with leather. Because dried parchment tends to assume the form it had before processing, the books were fitted with clasps or straps. During the later Middle Ages, when public libraries appeared, up to 18th century, books were often chained to a bookshelf or a desk to prevent theft. These chained books are called libri catenati. At first, books were copied mostly in bars, one at a time. With the rise of universities in the 13th century, the Manuscript culture of the time led to an increase in the demand for books, and a new system for copying books appeared. The books were divided into unbound leaves (pecia), which were lent out to different copyists, so the speed of book production was considerably increased. The system was maintained by secular stationers guilds, which produced both religious and non-religious material. Judaism has kept the art of the scribe alive up to the present. According to Jewish tradition, the Torah scroll placed in a synagogue must be written by hand on parchment, and a printed book would not do, though the congregation may use printed prayer books, and printed copies of the Scriptures are used for study outside the synagogue. A sofer (scribe) is a highly respected member of any observant Jewish community. The Arabs revolutionised the book’s production and its binding in the medieval Islamic world. They were the first to produce paper books after they learnt papermaking from the Chinese in the 8th century. Particular skills were developed for script writing (Arabic calligraphy), miniatures and bookbinding. The people who worked in making books were called Warraqin or paper professionals. The Arabs made books lighterâ€â€sewn with silk and bound with leather covered paste boards, they had a flap that wrapped the book up when not in use. As paper was less reactive to humidity, the heavy boards were not needed. The production of books became a real industry and cities like Marrakech, Morocco, had a street named Kutubiyyin or book sellers which contained more than 100 bookshops in the 12th century; the famous Koutoubia Mosque is named so because of its location in this street. In the words of Don Baker:

The medieval Islamic world also developed a unique method of reproducing reliable copies of a book in large quantities, known as check reading, in contrast to the traditional method of a single scribe producing only a single copy of a single manuscript, as was the case in other societies at the time. In the Islamic check reading method, only "authors could authorize copies, and this was done in public sessions in which the copyist read the copy aloud in the presence of the author, who then certified it as accurate." With this check-reading system, "an author might produce a dozen or more copies from a single reading," and with two or more readings, "more than one hundred copies of a single book could easily be produced." Modern paper books are printed on papers which are designed specifically for the publication of printed books. Traditionally, book papers are off white or low white papers (easier to read), are opaque to minimise the show through of text from one side of the page to the other and are (usually) made to tighter caliper or thickness specifications, particularly for case bound books. Typically, books papers are light weight papers 60 to 90 g/m² and often specified by their caliper/substance ratios (volume basis). For example, a bulky 80 g/m² paper may have a caliper of 120 micrometres (0.12 mm) which would be Volume 15 (120×10/80) where as a low bulk 80 g/m² may have a caliper of 88 micrometres, giving a volume 11. This volume basis then allows the calculation of a books PPI (printed pages per inch) which is an important factor for the design of book jackets and the binding of the finished book. Different paper qualities are used as book paper depending on type of book: Machine finished coated papers, woodfree uncoated papers, coated fine papers and special fine papers are common paper grades.

The intricate frontispiece of the Diamond Sutra from Tang Dynasty China, 868 AD (British Museum) In woodblock printing, a relief image of an entire page was carved into blocks of wood, inked, and used to print copies of that page. This method originated in China, in the Han dynasty (before 220AD), as a method of printing on textiles and later paper, and was widely used throughout East Asia. The oldest dated book printed by this method is The Diamond Sutra (868 AD). The method (called Woodcut when used in art) arrived in China in the early 14th century. Books (known as block-books), as well as playing-cards and religious pictures, began to be produced by this method. Creating an entire book was a painstaking process, requiring a hand-carved block for each page; and the wood blocks tended to crack, if stored for long. The monks or people who wrote them were paid highly. Main articles: Movable type and Incunabulum

"Selected Teachings of Buddhist Sages and Son Masters", the earliest known book printed with movable metal type, 1377. Bibliothèque nationale de France. The Chinese inventor Bi Sheng made movable type of earthenware circa 1045, but there are no known surviving examples of his printing. Metal movable type was invented in Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty (around 1230), but was not widely used: one reason being the enormous Chinese character set. Around 1450, in what is commonly regarded as an independent invention, Johannes Gutenberg invented movable type in Europe, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. This invention gradually made books less expensive to produce, and more widely available.

A 15th century incunabulum. Notice the blind-tooled cover, corner bosses and clasps. Early printed books, single sheets and images which were created before the year 1501 in Europe are known as incunabula. A man born in 1453, the year of the fall of Constantinople, could look back from his fiftieth year on a lifetime in which about eight million books had been printed, more perhaps than all the scribes of Europe had produced since Constantine founded his city in A.D. 330. Steam-powered printing presses became popular in the early 19th century. These machines could print 1,100 sheets per hour, but workers could only set 2,000 letters per hour. Monotype and linotype typesetting machines were introduced in the late 19th century. They could set more than 6,000 letters per hour and an entire line of type at once. The centuries after the 15th century were thus spent on improving both the printing press and the conditions for freedom of the press through the gradual relaxation of restrictive censorship laws. See also intellectual property, public domain, copyright. In mid-20th century, European book production had risen to over 200,000 titles per year. The methods used for the printing and binding of books continued fundamentally unchanged from the 15th century into the early years of the 20th century. While there was of course more mechanization, Gutenberg would have had no difficulty in understanding what was going on if he had visited a book printer in 1900. Gutenberg’s invention was the use of movable metal types, assembled into words, lines, and pages and then printed by letterpress. In letterpress printing ink is spread onto the tops of raised metal type, and is transferred onto a sheet of paper which is pressed against the type. Sheet-fed letterpress printing is still available but tends to be used for collector’s books and is now more of an art form than a commercial technique (see Letterpress).

The spine of the book is an important aspect in book design, especially in the cover design. When the books are stacked up or stored in a shelf, the details on the spine is the only visible surface that contains the information about the book. In stores, it is the details on the spine that attract buyers’ attention first. Today, the majority of books are printed by offset lithography in which an image of the material to be printed is photographically or digitally transferred to a flexible metal plate where it is developed to exploit the antipathy between grease (the ink) and water. When the plate is mounted on the press, water is spread over it. The developed areas of the plate repel water thus allowing the ink to adhere to only those parts of the plate which are to print. The ink is then offset onto a rubbery blanket (to prevent water from soaking the paper) and then finally to the paper.

Celsus Library was built in 135 AD and could house around 12,000 scrolls.

Books on library shelves with bookends, and call numbers visible on the spines Private or personal libraries made up of non-fiction and fiction books, (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) first appeared in classical Greece. In ancient world the maintaining of a library was usually (but not exclusively) the privilege of a wealthy individual. These libraries could have been either private or public, i.e. for people who were interested in using them. The difference from a modern public library lies in the fact that they were usually not funded from public sources. It is estimated that in the city of Rome at the end of the 3rd century there were around 30 public libraries. Public libraries also existed in other cities of the ancient Mediterranean region (e.g. Library of Alexandria). Later, in the Middle Ages, monasteries and universities had also libraries that could be accessible to general public. Typically not the whole collection was available to public, the books could not be borrowed and often were chained to reading stands to prevent theft. The beginning of modern public library begins around 15th century when individuals started to donate books to towns. The growth of a public library system in the United States started in the late 19th century and was much helped by donations from Andrew Carnegie. This reflected classes in a society: The poor or the middle class had to access most books through a public library or by other means while the rich could afford to have a private library built in their homes. The advent of paperback books in the 20th century led to an explosion of popular publishing. Paperback books made owning books affordable for many people. Paperback books often included works from genres that had previously been published mostly in pulp magazines. As a result of the low cost of such books and the spread of bookstores filled with them (in addition to the creation of a smaller market of extremely cheap used paperbacks) owning a private library ceased to be a status symbol for the rich. See also

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia : Publishing of books, magazines similar equipment |